Louisiana lawmakers have added two drugs commonly used in pregnancy and reproductive health care to the state’s list of controlled dangerous substances, a move that has alarmed doctors in the state.

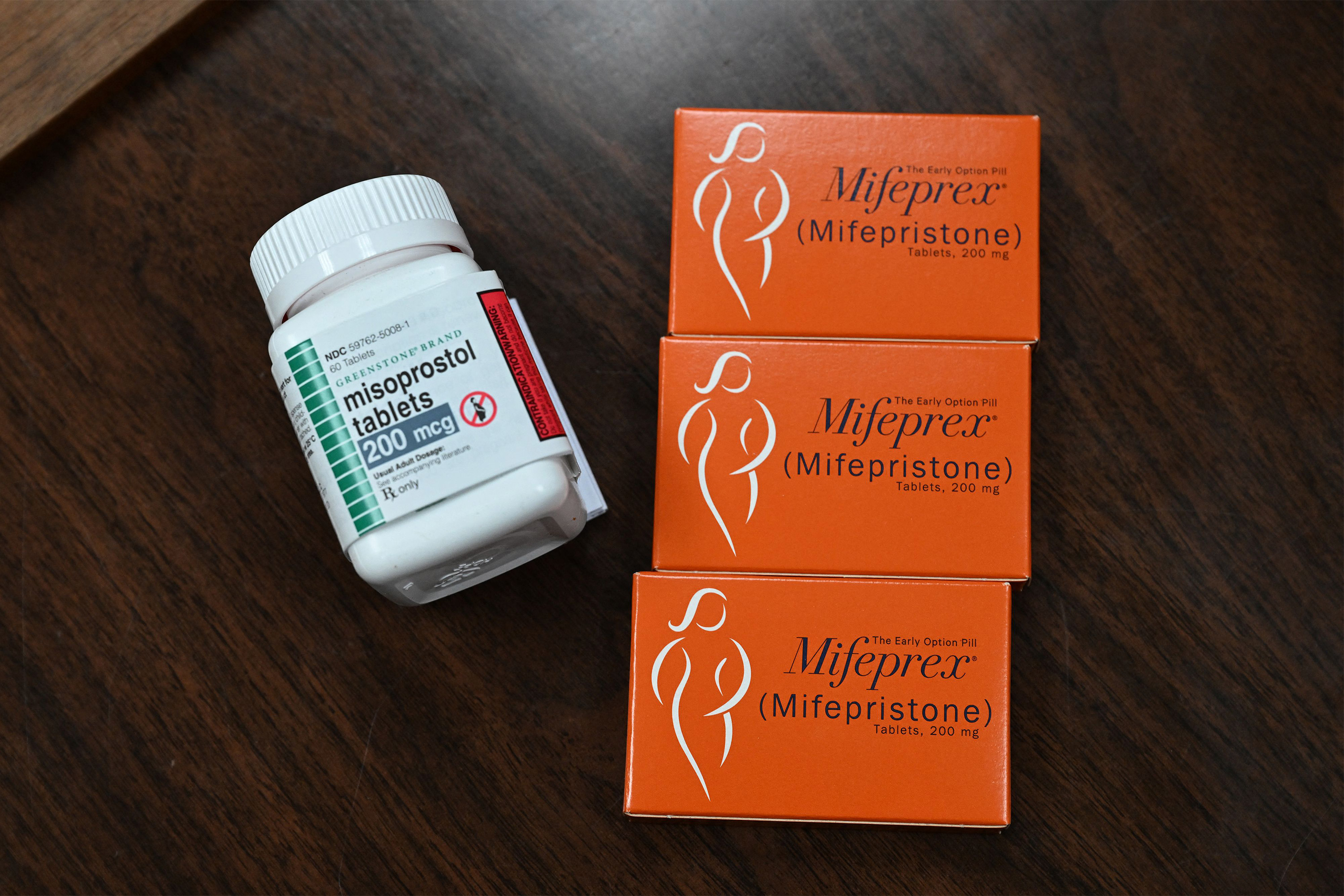

Mifepristone and misoprostol have many clinical uses, and one use approved by the FDA is to take the pills to induce an abortion at up to 10 weeks of gestation.

The bill that moved through the Louisiana Legislature this spring lists both medications as Schedule IV drugs under the state’s Uniform Controlled Dangerous Substances Law, creating penalties of up to 10 years in prison for anyone caught with the drugs without a valid prescription. Gov. Jeff Landry, a Republican, signed the bill into law in May. It takes effect Oct. 1.

The new law is the latest move by anti-abortion advocates trying to control access to abortion medications in states with near-total abortion bans, such as Louisiana. The law is the first of its kind, opening a new front in the state-by-state battle over reproductive medicine.

Republican-controlled states have passed various laws regulating medication abortion in the past, said Daniel Grossman, an OB-GYN and a reproductive health researcher at the University of California-San Francisco.

But after the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision in 2022, in which the Supreme Court ruled there was no constitutional right to an abortion, scrutiny of medication abortions escalated as clinics in certain states shuttered completely or were required to stop offering in-clinic procedures.

“It’s not surprising that states are trying everything they can to try to restrict these drugs,” Grossman said. “But this is certainly a novel approach.”

Before the Louisiana bill passed, more than 250 OB-GYNs and emergency, internal medicine, and other physicians from across the state signed a letter to the bill’s sponsor, state Sen. Thomas Pressly, a Republican, arguing the move could threaten women’s health by delaying lifesaving care.

“It’s just really jaw-dropping,” said Nicole Freehill, a New Orleans OB-GYN who signed the letter. “Almost a day doesn’t go by that I don’t utilize one or both of these medications.”

Mifepristone and misoprostol are routinely used to treat miscarriages, stop obstetric hemorrhaging, induce labor, or prepare the cervix for a range of procedures inside the uterus, such as inserting an IUD or taking a biopsy of the uterine lining.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Bill Born From a Family’s Misfortune

The proposal to reschedule the drugs as controlled dangerous substances was introduced as amendments to Pressly’s original bill creating the crime of “coerced criminal abortion” — where someone “knowingly” gives abortion pills to a pregnant woman to cause or attempt to cause an abortion “without her knowledge or consent.”

Pressly’s sister, Catherine Pressly Herring, testified at the hearing on the bill that she had been given abortion drugs without her knowledge by her former husband. Pressly said his sister’s story prompted the legislation.

In a statement, Pressly said that he added the new amendments to “control the rampant illegal distribution of abortion-inducing drugs.” He did not respond to requests for comment.

“By placing these drugs on the controlled substance list, we will assist law enforcement in protecting vulnerable women and unborn babies,” Pressly wrote in this statement.

Louisiana Right to Life, the state’s most influential anti-abortion group, helped draft the bill. And the group’s communications director, Sarah Zagorski, said that claims that rescheduling the drugs as dangerous could harm women’s health are “fearmongering.”

The real problem, she said, is that mifepristone and misoprostol are too accessible in Louisiana and are being used to induce abortions despite the state’s ban.

“We’ve had pregnancy centers email us with many stories of minors getting access to this medication,” Zagorski said.

Studies have shown a surge in the ordering of abortion pills online in states that have severe restrictions on abortion.

In the Louisiana Legislature committee hearing on the bill, anti-abortion advocates said that physicians would still be allowed to dispense mifepristone and misoprostol for lawful medical care, and that women who give themselves abortions using the medications would be exempted from criminal liability.

“Under this law, or any abortion law, in Louisiana we see the woman as often the second victim,” testified Dorinda Plaisance, a lawyer who works with Louisiana Right to Life. “And so Louisiana has chosen to criminalize abortion providers” rather than women who use the medications for their own abortions.

Move ‘Not Scientifically Based,’ Doctors Say

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration and individual states have the power to list drugs as controlled dangerous substances.

State and federal regulations aim to control access to drugs, such as opioids, based on their medical benefit and their potential for abuse, according to Joseph Fontenot, executive director of the Louisiana Board of Pharmacy, the agency that monitors drugs listed as controlled dangerous substances.

Like other states, Louisiana tracks prescriptions in databases that include the name of the patient, the health provider who wrote the prescription, and the dispensing pharmacy.

Physicians need a special license to prescribe the drugs — in 2023, there were 18,587 physicians in Louisiana, 13,790 of whom had a license to prescribe controlled dangerous substances, according to data from the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners and the Board of Pharmacy.

“Every state has a prescription drug monitoring program. And they really are designed to identify prescription drug mills that are hawking fentanyl and opioid painkillers,” said Robert Mikos, a professor of law and a drug policy expert at Vanderbilt University.

What happened to Pressly’s sister — being tricked into taking mifepristone or misoprostol — is a form of drug abuse, said Zagorski of Louisiana Right to Life, which is why the drugs should be more strictly controlled.

But Fontenot, of the Louisiana Board of Pharmacy, said that under Louisiana’s law, abuse refers to addiction. Jennifer Avegno, a New Orleans emergency physician and the director of the New Orleans Health Department, agrees. “There is no risk of someone getting hooked on misoprostol,” Avegno said.

Under the new law, mifepristone and misoprostol will be added to a list comprised of opioids, depressants, and stimulants. “To classify these medications as a drug of abuse and dependence in the same vein as Xanax, Valium, Darvocet is not only scientifically incorrect, but [a] real concern for limiting access to these drugs,” Avegno said.

Doctors worry that the bill could set a dangerous precedent for state officials who want to restrict access to any drug they consider dangerous or objectionable, regardless of its addictive potential, Avegno said.

Fears Over Delays in Care

In their letter opposing the reclassification, doctors said the “false perception that these are dangerous drugs” could lead to “fear and confusion among patients, doctors, and pharmacists, which delays care and worsens outcomes” in a state with high rates of maternal injury and death.

The increased scrutiny could have a statewide chilling effect and make doctors, pharmacists, and even patients more reluctant to use these drugs, the doctors wrote.

The state database allows any doctor or pharmacist to look up the prescription history of his or her patient. The data is also accessible by the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners, which licenses physicians and other providers, and by law enforcement agencies with a warrant.

“Could I be investigated for my use of misoprostol? I don’t know,” said Freehill, the New Orleans OB-GYN.

Pharmacists could become more reluctant to dispense the medications, Freehill said, exacerbating a problem she and other OB-GYNs have been dealing with since Louisiana banned nearly all abortions. That reluctance could lead to patients miscarrying without timely treatment.

“They could be sitting there bleeding, increasing their risk that they would have a dangerous amount of blood loss” or risking infection, she said.

Before the bill passed, Freehill routinely phoned in every prescription for misoprostol when her patients were miscarrying so she could explain to the pharmacist why she was prescribing it. Once the bill goes into effect in the fall and the drug becomes a controlled dangerous substance, that will no longer be possible because those types of prescriptions must be written on a pad or sent electronically.

In hospitals, the drugs will also have to be locked away. That could potentially cause delays getting the drug when a patient is hemorrhaging after childbirth.

Doctors worry some patients might be afraid to take the medications once they’re listed as dangerous, Avegno said.

In a written response to the Louisiana physicians who signed the protest letter, Pressly said the doctors whom he’s spoken with feel the bill “will not harm health care for women.”

Criminalizing Support for Abortions

Louisiana’s abortion ban already makes it a crime to provide an abortion, including by giving someone medications used to induce abortion. And a 2022 law added up to 50 years in prison for mailing mifepristone or misoprostol.

Because the new law explicitly exempts pregnant women, opponents like Elizabeth Ling believe it is meant to isolate those women from others who would help them. Ling, a reproductive rights attorney at If/When/How, is particularly concerned about the prison penalties, which she believes are intended to frighten and disrupt underground networks of support for patients seeking the pills.

Pregnant patients might worry about ordering online or enlisting a friend to help obtain the pills: “Is my friend who is simply just providing me emotional support going to somehow, you know, be punished for doing that?” Ling said.

Ling added that there’s concern that the law could also be used to target people who aren’t pregnant but who want to order abortion pills online and stock them in case of a future pregnancy. That practice has become increasingly popular in states with abortion bans.

This article is from a partnership that includes WWNO, NPR, and KFF Health News.