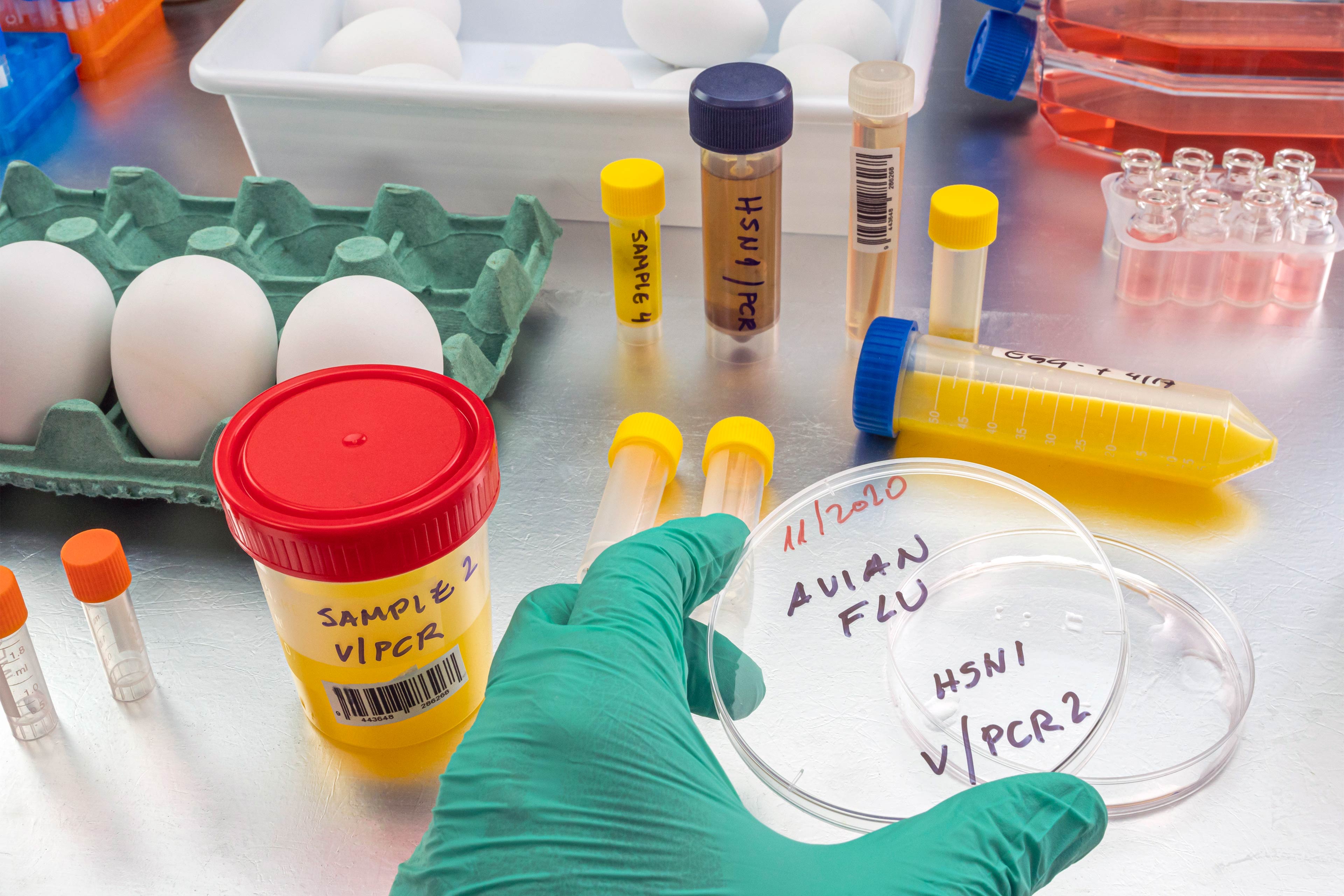

Headlines are flying after the Department of Agriculture confirmed that the H5N1 bird flu virus has infected dairy cows around the country. Tests have detected the virus among cattle in nine states, mainly in Texas and New Mexico, and most recently in Colorado, said Nirav Shah, principal deputy director at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at a May 1 event held by the Council on Foreign Relations.

A menagerie of other animals have been infected by H5N1, and at least one person in Texas. But what scientists fear most is if the virus were to spread efficiently from person to person. That hasn’t happened and might not. Shah said the CDC considers the H5N1 outbreak “a low risk to the general public at this time.”

Viruses evolve and outbreaks can shift quickly. “As with any major outbreak, this is moving at the speed of a bullet train,” Shah said. “What we’ll be talking about is a snapshot of that fast-moving train.” What he means is that what’s known about the H5N1 bird flu today will undoubtedly change.

With that in mind, KFF Health News explains what you need to know now.

Q: Who gets the bird flu?

Mainly birds. Over the past few years, however, the H5N1 bird flu virus has increasingly jumped from birds into mammals around the world. The growing list of more than 50 species includes seals, goats, skunks, cats, and wild bush dogs at a zoo in the United Kingdom. At least 24,000 sea lions died in outbreaks of H5N1 bird flu in South America last year.

What makes the current outbreak in cattle unusual is that it’s spreading rapidly from cow to cow, whereas the other cases — except for the sea lion infections — appear limited. Researchers know this because genetic sequences of the H5N1 viruses drawn from cattle this year were nearly identical to one another.

The cattle outbreak is also concerning because the country has been caught off guard. Researchers examining the virus’s genomes suggest it originally spilled over from birds into cows late last year in Texas, and has since spread among many more cows than have been tested. “Our analyses show this has been circulating in cows for four months or so, under our noses,” said Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Q: Is this the start of the next pandemic?

Not yet. But it’s a thought worth considering because a bird flu pandemic would be a nightmare. More than half of people infected by older strains of H5N1 bird flu viruses from 2003 to 2016 died. Even if death rates turn out to be less severe for the H5N1 strain currently circulating in cattle, repercussions could involve loads of sick people and hospitals too overwhelmed to handle other medical emergencies.

Although at least one person has been infected with H5N1 this year, the virus can’t lead to a pandemic in its current state. To achieve that horrible status, a pathogen needs to sicken many people on multiple continents. And to do that, the H5N1 virus would need to infect a ton of people. That won’t happen through occasional spillovers of the virus from farm animals into people. Rather, the virus must acquire mutations for it to spread from person to person, like the seasonal flu, as a respiratory infection transmitted largely through the air as people cough, sneeze, and breathe. As we learned in the depths of covid-19, airborne viruses are hard to stop.

That hasn’t happened yet. However, H5N1 viruses now have plenty of chances to evolve as they replicate within thousands of cows. Like all viruses, they mutate as they replicate, and mutations that improve the virus’s survival are passed to the next generation. And because cows are mammals, the viruses could be getting better at thriving within cells that are closer to ours than birds’.

The evolution of a pandemic-ready bird flu virus could be aided by a sort of superpower possessed by many viruses. Namely, they sometimes swap their genes with other strains in a process called reassortment. In a study published in 2009, Worobey and other researchers traced the origin of the H1N1 “swine flu” pandemic to events in which different viruses causing the swine flu, bird flu, and human flu mixed and matched their genes within pigs that they were simultaneously infecting. Pigs need not be involved this time around, Worobey warned.

Q: Will a pandemic start if a person drinks virus-contaminated milk?

Not yet. Cow’s milk, as well as powdered milk and infant formula, sold in stores is considered safe because the law requires all milk sold commercially to be pasteurized. That process of heating milk at high temperatures kills bacteria, viruses, and other teeny organisms. Tests have identified fragments of H5N1 viruses in milk from grocery stores but confirm that the virus bits are dead and, therefore, harmless.

Unpasteurized “raw” milk, however, has been shown to contain living H5N1 viruses, which is why the FDA and other health authorities strongly advise people not to drink it. Doing so could cause a person to become seriously ill or worse. But even then, a pandemic is unlikely to be sparked because the virus — in its current form — does not spread efficiently from person to person, as the seasonal flu does.

Q: What should be done?

A lot! Because of a lack of surveillance, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and other agencies have allowed the H5N1 bird flu to spread under the radar in cattle. To get a handle on the situation, the USDA recently ordered all lactating dairy cattle to be tested before farmers move them to other states, and the outcomes of the tests to be reported.

But just as restricting covid tests to international travelers in early 2020 allowed the coronavirus to spread undetected, testing only cows that move across state lines would miss plenty of cases.

Such limited testing won’t reveal how the virus is spreading among cattle — information desperately needed so farmers can stop it. A leading hypothesis is that viruses are being transferred from one cow to the next through the machines used to milk them.

To boost testing, Fred Gingrich, executive director of a nonprofit organization for farm veterinarians, the American Association of Bovine Practitioners, said the government should offer funds to cattle farmers who report cases so that they have an incentive to test. Barring that, he said, reporting just adds reputational damage atop financial loss.

“These outbreaks have a significant economic impact,” Gingrich said. “Farmers lose about 20% of their milk production in an outbreak because animals quit eating, produce less milk, and some of that milk is abnormal and then can’t be sold.”

The government has made the H5N1 tests free for farmers, Gingrich added, but they haven’t budgeted money for veterinarians who must sample the cows, transport samples, and file paperwork. “Tests are the least expensive part,” he said.

If testing on farms remains elusive, evolutionary virologists can still learn a lot by analyzing genomic sequences from H5N1 viruses sampled from cattle. The differences between sequences tell a story about where and when the current outbreak began, the path it travels, and whether the viruses are acquiring mutations that pose a threat to people. Yet this vital research has been hampered by the USDA’s slow and incomplete posting of genetic data, Worobey said.

The government should also help poultry farmers prevent H5N1 outbreaks since those kill many birds and pose a constant threat of spillover, said Maurice Pitesky, an avian disease specialist at the University of California-Davis.

Waterfowl like ducks and geese are the usual sources of outbreaks on poultry farms, and researchers can detect their proximity using remote sensing and other technologies. By zeroing in on zones of potential spillover, farmers can target their attention. That can mean routine surveillance to detect early signs of infections in poultry, using water cannons to shoo away migrating flocks, relocating farm animals, or temporarily ushering them into barns. “We should be spending on prevention,” Pitesky said.

Q: OK it’s not a pandemic, but what could happen to people who get this year’s H5N1 bird flu?

No one really knows. Only one person in Texas has been diagnosed with the disease this year, in April. This person worked closely with dairy cows, and had a mild case with an eye infection. The CDC found out about them because of its surveillance process. Clinics are supposed to alert state health departments when they diagnose farmworkers with the flu, using tests that detect influenza viruses, broadly. State health departments then confirm the test, and if it’s positive, they send a person’s sample to a CDC laboratory, where it is checked for the H5N1 virus, specifically. “Thus far we have received 23,” Shah said. “All but one of those was negative.”

State health department officials are also monitoring around 150 people, he said, who have spent time around cattle. They’re checking in with these farmworkers via phone calls, text messages, or in-person visits to see if they develop symptoms. And if that happens, they’ll be tested.

Another way to assess farmworkers would be to check their blood for antibodies against the H5N1 bird flu virus; a positive result would indicate they might have been unknowingly infected. But Shah said health officials are not yet doing this work.

“The fact that we’re four months in and haven’t done this isn’t a good sign,” Worobey said. “I’m not super worried about a pandemic at the moment, but we should start acting like we don’t want it to happen.”